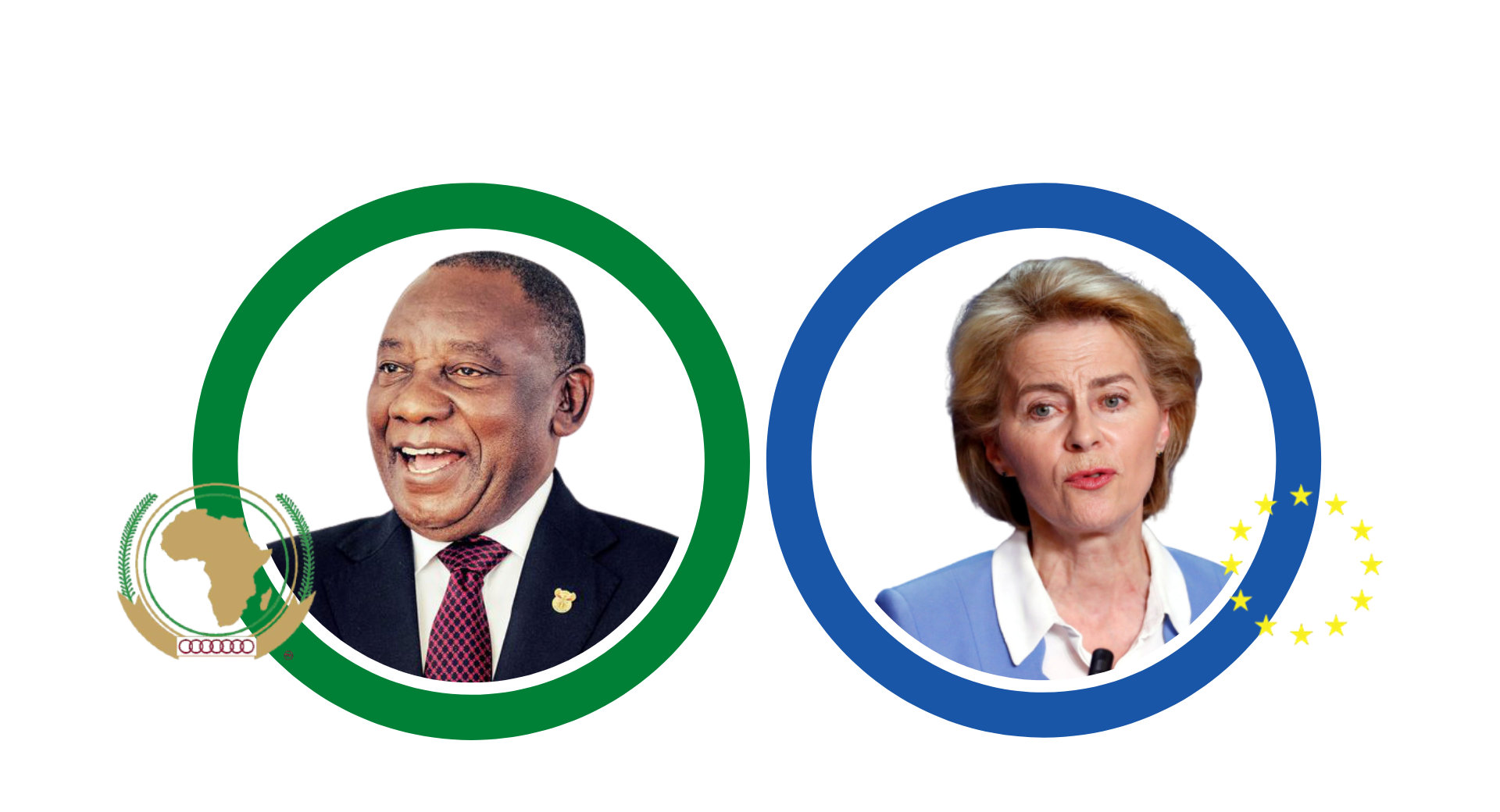

The African Union may bear similarities in name and objective with the European Union, but there is a great disparity between the socio-economic fortunes of the former and the latter. Have a look at why one prospers while the other struggles.

Ideas.memo | Fifehan Ogunde Ph.D

The European Union (EU) was formed in 1950, only 13 years before the Organization of African Unity (OAU) was established in 1963. The OAU was replaced in 2002 with the African Union (AU) to achieve greater unity between African countries and accelerate socio-economic development. 70 years after the formation of the EU and 57 years after the formation of the OAU (now AU), their economic and political status could not be more different.

While the EU, with a membership of 28 states, has a GDP of over US$15.9 trillion, the AU with a membership of 52 countries only has a GDP of US$2.5 trillion. The European Union is the world’s largest trade block, being the world’s biggest exporter and the biggest import market for over 100 countries. In the context of global political influence, the story is similar. Nearly 25% of the major international organizations are headed by representatives of EU countries. Tijani Mohammed-Bande, a Nigerian national, is the only representative from the AU as the current President of the United Nations General Assembly.

Why is this the case?

A number of reasons can be suggested. While the creation of the European Union has led to increased socio-economic integration through the free movement of goods and persons in the European Economic Area (EEA), inter-state movement of goods and persons remains a challenge across Africa. Africans can only travel visa-free to about a quarter of other African Countries.

It was only in December 2019 that Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy, announced that African passport holders could apply for a visa upon arrival in the country. A protocol establishing the African Economic Community relating to the free movement of goods and persons, adopted in 2018, is not yet in force and has only been ratified by four African countries. In fact, it is easier to transport goods and services from certain African countries to Europe and Asia than other African Countries.

In addition, the judicial and quasi-judicial institutions established in the AU and EU have enjoyed contrasting fortunes. The EU has been able to develop a strong supra-national justice and human rights enforcement framework through different treaties, in particular the Treaty of the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights have played significant roles in strengthening international law.

On the other hand, the institutions established by the African Union to exercise oversight over the actions of member state governments have struggled to establish legitimacy. The African Commission on Human Rights, established to enforce the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, is bedeviled with problems of inadequate resources and limited technical expertise. The African Court of Human Rights (ACtHr), established by a protocol that came into force in 2004 has jurisdiction to receive cases from only 9 of the 30 African states that have ratified the protocol.

Over 40% of AU member states do not pay their yearly contributions to the AU and the majority of the AU’s budget is funded by foreign donors including the EU, China, USA, and the World Bank.

Furthermore, unlike many of the countries in the EU, many African countries operate pseudo-democratic/authoritarian regimes characterized by limited press freedom, human rights violations, and protectionist trade policies. It has also been noted how the African Union has been unable to intervene as a peacemaker in conflict-ridden regions, providing little more than moral or diplomatic encouragement in intra-African conflict. The AU has also been unable to stop the violent actions of past military dictators.

Looking ahead: a progressive African Union

The relative success of the EU as a supranational organization is not an accident. Member states have over the years, strengthened the union by supporting its existing institutions, both financially and politically. The UK, France, Italy, and Germany alone for instance contributed a total of 75 billion euros to the EU in 2019. Admittedly, the largest economy in Africa, Nigeria, is only the 27th largest in the world, and it is unrealistic to assume that remittances from AU member states to the AU would be on a similar scale to the EU. Nevertheless, African countries as a whole need to be more deliberate about supporting the AU and its existent institutions, particularly financially.

Over 40% of AU member states do not pay their yearly contributions to the AU and the majority of the AU’s budget is funded by foreign donors including the EU, China, USA, and the World Bank. It is noted that the AU has been taking steps towards financial autonomy. In 2016, the AU adopted the Kigali Decision under which 0.2% of eligible imports of member states are to be remitted to the African Union. As at 2018, only 16 member states were collecting such levies.

The AU has also been unable to stop the violent actions of past military dictators.

African states also need to enhance the political legitimacy of the AU by complying with decisions of the ACtHR and the ACHR, as well as incorporate AU treaties into domestic law. Researchers have noted that only 14% of African states comply fully with the decisions of the ACHR. While compliance with decisions of judicial or quasi-judicial decisions is also a problem even in the EU, it is noted that up to 60% of decisions by the European Court of Human Rights on freedom of expression and 40% of decisions on discrimination have been complied with by member states. There is room for great improvement by African countries in this regard.

It is also imperative that key states in the African Union step up to the plate in changing the narrative relating to African countries in global politics. The African region is often associated, and rightly so, with political instability, corruption, and autocratic rule. Resolving existing conflicts and political tension in areas such as the Central African Republic, Mali, and Cameroon for instance is fundamental in changing this narrative.

On the economic front, larger economies such as Nigeria need to convert their human capital advantage into significant economic development through investment in infrastructure and education. Emerging economies such as Ghana, Ethiopia, Senegal, and Ivory Coast should ensure their economic promise is matched with corresponding investment in key sectors of economic development, particularly in the areas of education and infrastructure. Most importantly, all these economies need to work together as a unit to boost the economic profile of the AU and its institutions.

The African Union may bear similarities in name and objective with the European Union, but there is a great disparity between the socio-economic fortunes of the former and the latter.

The opinions expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of borg.

The ideas expressed qualifies as copyright and is protected under the Berne Convention.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is notified.

©2020 borg. Legal & Policy Research