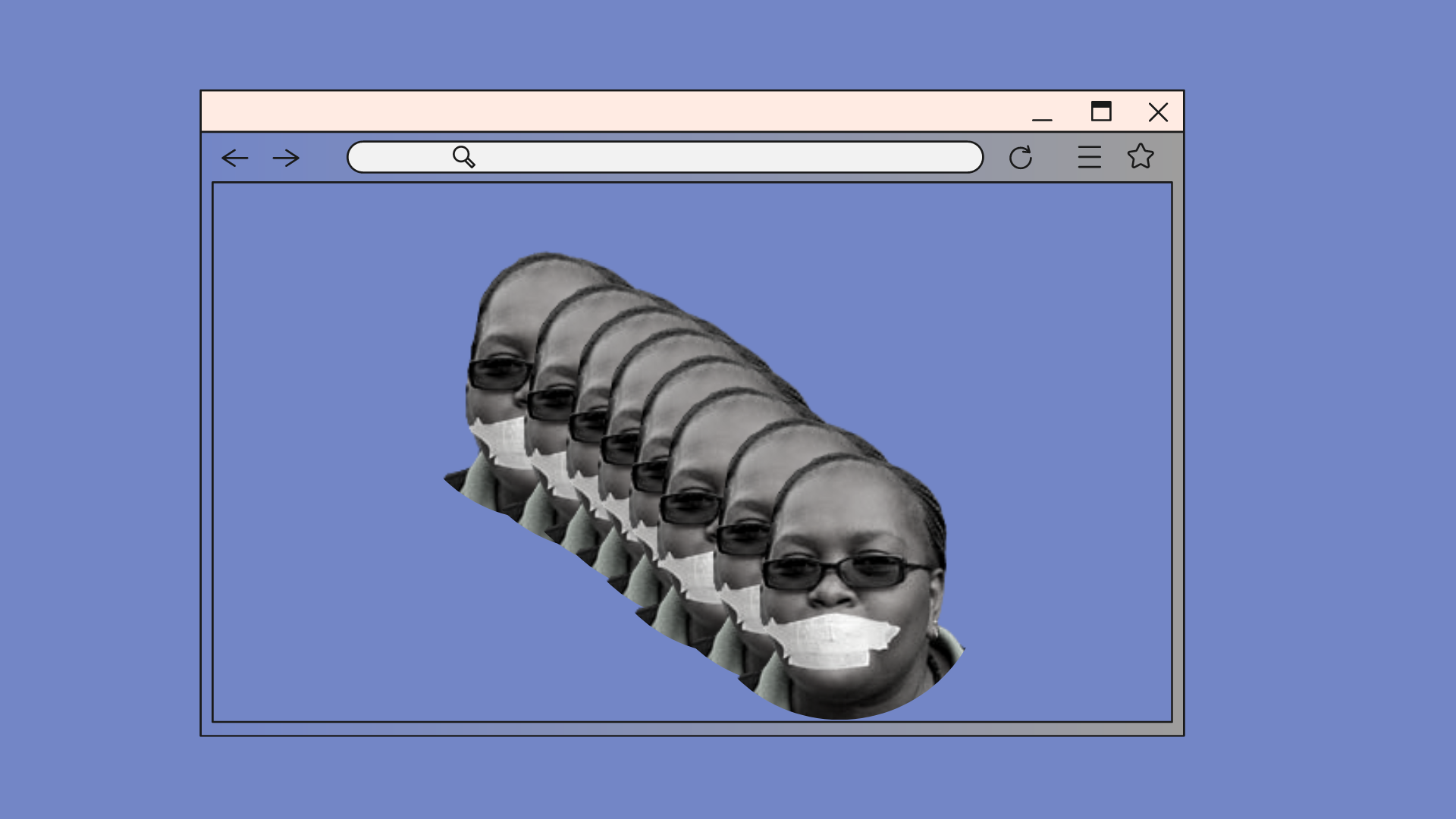

In the second of our two-part series, this commentary proposes an integrated approach towards combating the prevalent issue of internet shutdowns in Africa, based on multistakeholder ideals.

The Limits of Existing Interventions

As Internet shutdowns continue to occur in Africa, there has been no shortage of efforts to resist them. So far, most approaches to combating internet shutdowns in Africa take the form of decentralised protests by affected users, culminating either in actual demonstrations or deliberate attempts to bypass shutdown measures, such as the use of virtual private networks.

They also take the form of agitations and advocacy led by local and international civic society organisations or strategic litigation before national and supranational panels by internet advocacy bodies.

These approaches each suffer inherent limitations. Operating these interventions in isolation often only addresses parts of the problem where they yield any results in the first place. For example, where agitations can help restore the internet after it has been shut down, they are “after the fact” and are unlikely to prevent internet shutdowns or stop the government from achieving the ulterior purposes behind shutdowns.

Similarly, where litigation helps restate the obligation of states to protect the interest of the citizenry or to admonish states for human rights violations through internet shutdowns, they themselves hardly enforced (or enforceable) and rarely impact whether states will resort to internet shutdowns again. User attempts at bypassing internet shutdown measures help combat shutdowns while they are ongoing but are not particularly useful in addressing the policy and governance failures that culminate in internet shutdowns, while general advocacy relies too much on the willingness of governments to listen.

Multistakeholderism and Co-creation as a Policy Approach

The inherent limitations of available responses to internet shutdowns can be addressed by operating complementary interventions at the same time. This is because, due to the multidimensional nature of the issue of internet shutdowns, there is a need for synchronisation across stakeholder gro to achieve the best range of results consistently. The case, therefore, for multi-strategy and multistakeholder approaches to combating internet shutdowns is self-apparent.

Through multistakeholder cooperation, local stakeholders in the internet community cutting a broad foundation of interested parties – including businesses, technical experts, civil society, governments and everyday users – can come together to work in conjunction towards achieving consensus and implementing complementary strategic and proactive approaches to the problem of internet shutdowns.

Moreover, a multistakeholder approach to combating internet shutdowns opens new fronts for combating the problem, which may not be available or accessible to any individual or group actors in isolation, such as the possibility of dialogue with governments towards co-regulation strategies or collaboration to develop the diversity of internet connectivity to limit government power to shut down the internet through “kill switches.”

Implementing Multistakeholderism

The first and most vital step towards achieving multistakeholder collaboration, whether in the form of multistakeholder processes or cooperation, is establishing lines of communication. Local internet communities must develop channels of communication that allow for integration, collaboration, and open engagement across stakeholders. This can be done by utilising existing Internet governance structures and networks, such as the local Internet Society community or the Local Internet Governance Forum (IGF) meetings to congregate stakeholders and build collective approaches to combat internet shutdowns locally.

Another way this can be achieved would be through developing inclusive multistakeholder coalitions specifically for addressing issues of internet shutdowns, through which fora collective action can be fostered. Already, citizens in African countries affected by or prone to internet shutdowns have started to form multi-stakeholder coalitions that support internet freedom. These coalitions not only rest internet shutdowns, but also pressure governments and other actors to create, abide by, and respect policies that promote internet freedom.

Mapping Multistakeholder Collaboration for Combating Internet Shutdowns

Stakeholder One: Private Sector

Private actors, such as telecommunications companies, internet service providers and technology companies, should work in tandem with civic society organisations (“CSOs”) in advocating against using internet service providers as handmaids for internet shutdowns and throttling. They can also collaborate with CSOs and the technical community to request governments to clarify their expectations on network control and agree on a predetermined modus of operation in respect of blocking orders, which can be insisted on in the event of unusual requests by the governments.

They can also adopt transparency measures and due diligence mechanisms based on enhanced understanding and collaboration with CSOs, research actors, non-governmental bodies, and others to support the availability of clear information regarding internet shutdowns. They can further engender support for their engagements with governments in the face of shutdown requests by leveraging international collaboration and support. For example, the Global Network Initiative (GNI) has developed a mechanism for local ISPs to report when they receive unconventional demands from the government.

Also, membership in the International Telecommunication Union now includes technology and telecommunications companies. Local companies may be able to utilise this forum to support technical advocacy, restate issues and garner international sponsorship in combating internet shutdowns, with support from advocacy organisations.

Stakeholder Two: Civic Society Organisations

CSOs can collaborate with internet service providers and telecommunications companies to better understand the technical mechanisms available to the government for internet disruption and, in so doing, better drive more concerted conversations on limiting government control over internet infrastructure, whether by ensuring autonomy and privatisation of internet service providers, strengthening of licensing and regulatory frameworks to ensure licensing cannot be arbitrarily revoked, grounding justifications to interfere with networks in law, creating legal barriers to network disruption (such as requiring court authorisation for orders affecting network access), the democratisation of management of internet infrastructure, preventing or advocating against the creation of single internet gateways or “choke points etc.”

They may also be able to collaborate with human rights organisations and non-governmental bodies to undertake litigation against governments and government bodies before national or supranational courts upon suspicion of possible internet shutdowns or following internet shutdowns, as well as collaborate with international governmental organisations to assert pressure on governments to comply with court decisions in this respect.

Civic society organisations can also work in conjunction with academia and the government stakeholder to better understand the precipitating factors behind internet shutdowns and understand how best to resolve underlying frictions, whether through championing the development of balanced partial platform regulation legislations or by bridging the conversation between government and internet platforms, towards cooperation in fighting issues of hate speech, fake news, disinformation or political propaganda, that may otherwise entice government into internet restriction.

Stakeholder Three - Governments

The government stakeholder groups can work with the civic society stakeholder groups and users to better understand the human rights issues posed by internet shutdowns, the inefficiencies of internet restriction measures and better ways to address genuine public policy concerns resulting from internet activities. Governments can, in collaboration with civic society organisations, non-governmental organizations, human rights organisations, private sector, among other actors, establish clear policies on the operation of local laws within cyberspace.

Democratic governments of other countries can also play support roles in influencing the actions of governments adopting internet shutdowns, such as by helping establish clear multilateral norms regarding prohibitions against internet shutdowns and long-term internet controls; issuing consistent public condemnations against internet shutdowns; and creating multilateral entities responsible for codifying and enforcing policy standards.

They can also discourage restrictive actions by such governments by adopting foreign policy stances that decry internet shutdowns and disruptions (such as adopting economic sanctions to influence state decisions) and by working with local civic society organisations and private actors to support citizens during shutdowns such as through the provision of circumvention tools, alternative means of internet access and “internet refugee” stations.

Stakeholder Four – International Bodies

International bodies can also play a major role as stakeholders in the internet community. While bodies like the Economic Community of West African States have been explicit in their stance on internet shutdowns, through decisions such as that in Amnesty International Togo and Ors v. The Togolese Republic and recently, in respect of the Twitter Ban in Nigeria, more international bodies with interest in the internet need to get involved in safeguarding the internet from unlawful shutdowns.

International Governmental Organisations can collaborate with local CSOs, platform service providers and technology companies to push for the adoption of international statutes protecting the right to access and use the internet, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), the Global Network Initiative (GNI) Principles, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 21 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

They can also work in conjunction with other democratic governments to enforce the obligations of state members concerning online freedoms, as well as to implement international sanctions against member states which use shutdowns to curb these freedoms.

Conclusion

Irrespective of what form they take, internet shutdowns present the same series of challenges to society and the internet community – they threaten the internet’s purpose of connecting all people, truncate the principles of openness and freedom of access (which constitute the philosophical backbone of the internet) and severely hamper the internet rights and freedoms of the people affected by them. They also accentuate the global internet community’s concerns around internet fragmentation, compromise the security, safety and resilience of the internet, and are enduring evidence of a failure of accountability on the part of state actors.

The challenges presented by internet shutdowns and the emergence of digital authoritarianism in Africa compound the policy issues already facing the internet and detract from the further development of the internet in the continent. It is important, therefore, not as a matter of luxury, but as a necessity, that measures which have the effect of preventing internet shutdowns or nullifying/limiting the impact of attempts at internet shutdowns in Africa be eagerly embraced.

Already, multistakeholder processes and approaches have proven to be best suited to address policy issues affecting the internet, considering the policy and technical complexities of the internet. Some of the approaches identified in this commentary can serve as a bedrock for developing comprehensive multistakeholder collaboration and co-creation strategies for use by local internet communities. In establishing local strategies, references should be made to the unique local contexts and the priorities driving collaboration. The successes of local responses in the next few years may well determine the future of the internet in Africa.

Author

Vincent Okonkwo | Lead Research Analyst, Tech and Innovation Policy | v.o@borg.re