Ideas.memo | Nelson Obike

Nigeria ticks all the boxes in the standard checklist for “prerequisites of federalism” but seems to have a far from impressive scorecard for “practitioners of true federalism”. Decentralization check - true state autonomy uncheck, heterogeneity check - administrative cohesion uncheck, population size check - development and citizen inclusion uncheck.

It is clear that the Nigerian federal structure passes the basic face value test of what a federal state should have but fails on many fronts when it comes to the proper test of a model federal state. The reasons for this are not hard to find; the streak of over-dependent federating units, unclear divisions of powers between federating units, disproportionate power-sharing lists amongst the federating units, and of course constant intermeddling between and amongst respective federating units are some of the highlights of a faulty and dodgy arrangement we operate as a federal government/state.

A major manifestation of this defect is the obvious shortfall in developmental pace and cycles of federating units. Many states are largely reliant on the central government for survival and doing too little to pursue self-sufficiency while others suffer from legal and constitutional strictures that hamper innovation and deter creativity in revenue sourcing for most states within the federal structure. This revenue concern has had huge knock-on effects on the constituent states and their indigenous population with too little at the disposal of many states to meet domestic needs while also battling the incessant plague of corruption in its many forms. The “Restructuring” argument has probably gathered momentum, as a fallout of agitation and exasperation with the Nigerian story, from the advocates of stronger federating units with greater control of their resources and how it is spent and disbursed.

A re-arrangement of some sorts of the present federal structure begins from nowhere else but in the power-sharing agreement that is stamped with the authority and approval of the 1999 constitution. The first, second, and fourth schedule of this document spells out who can do what and are also instructive in determining how far these powers can be exercised by the federating units.

On the one hand, most of the actual powers of the state or second-tier units have been skewed towards the federal government, a contradiction by the standards of all model federalist states, while on the other hand the state government continually strips or intermeddles in the exercise of powers and functions constitutionally assigned to the local/grassroots government, which is yet another anomaly.

Unfortunately, the latter anomaly has resulted in a governance structure where most local governments into mere extensions of the state government with little or no autonomy even in choosing its administrators despite constitutionally circumscribed powers.

With depleting revenue inflow and a population growing exponentially alongside developmental deficits, it becomes clear that there is an urgent need to review the apportionment of power and responsibility within the Nigerian federal and state structure.

From the clear outline of this structure, it becomes clear and evident that the structure and division of powers agreement remains a glaring comedy of errors and a mismatch of governmental priorities. With depleting revenue inflow and a population growing exponentially alongside developmental deficits, it becomes clear that there is an urgent need to review the apportionment of power and responsibility within the Nigerian federal and state structure. To make this happen, these are suggested steps in what we believe to be the right direction.

Unbundling the constitutional powers of federating units

It goes without saying that beyond any pretensions or falsities, the federal government is a belaboured federating unit with so much to do, in so little time and with lean resources to do it. There is obviously a need to review and decongest the exclusive list to reflect existing realities; a power-sharing model and joint exercise of some of these powers may be the best way to address some of the deficits and vacuums that persist in the exercise of these powers which have been punctuated by unevenness in commitment and political will by administrators and outright abandonment in most instances.

States, with buoyant balance sheets and fairly manageable populations, can undertake jointly sanctioned projects which are co-financed by either the state or federal government with the common goal of facilitating some form of load shedding for the federal government and ensuring that development becomes a more widespread and palpable denominator across the country.

On the other hand, an outright delegation of powers to the state government may be advised in certain instances, on the basis of strength and capacity across board, while the central government retains its powers of review, control, and regulation which is to be fairly exercised

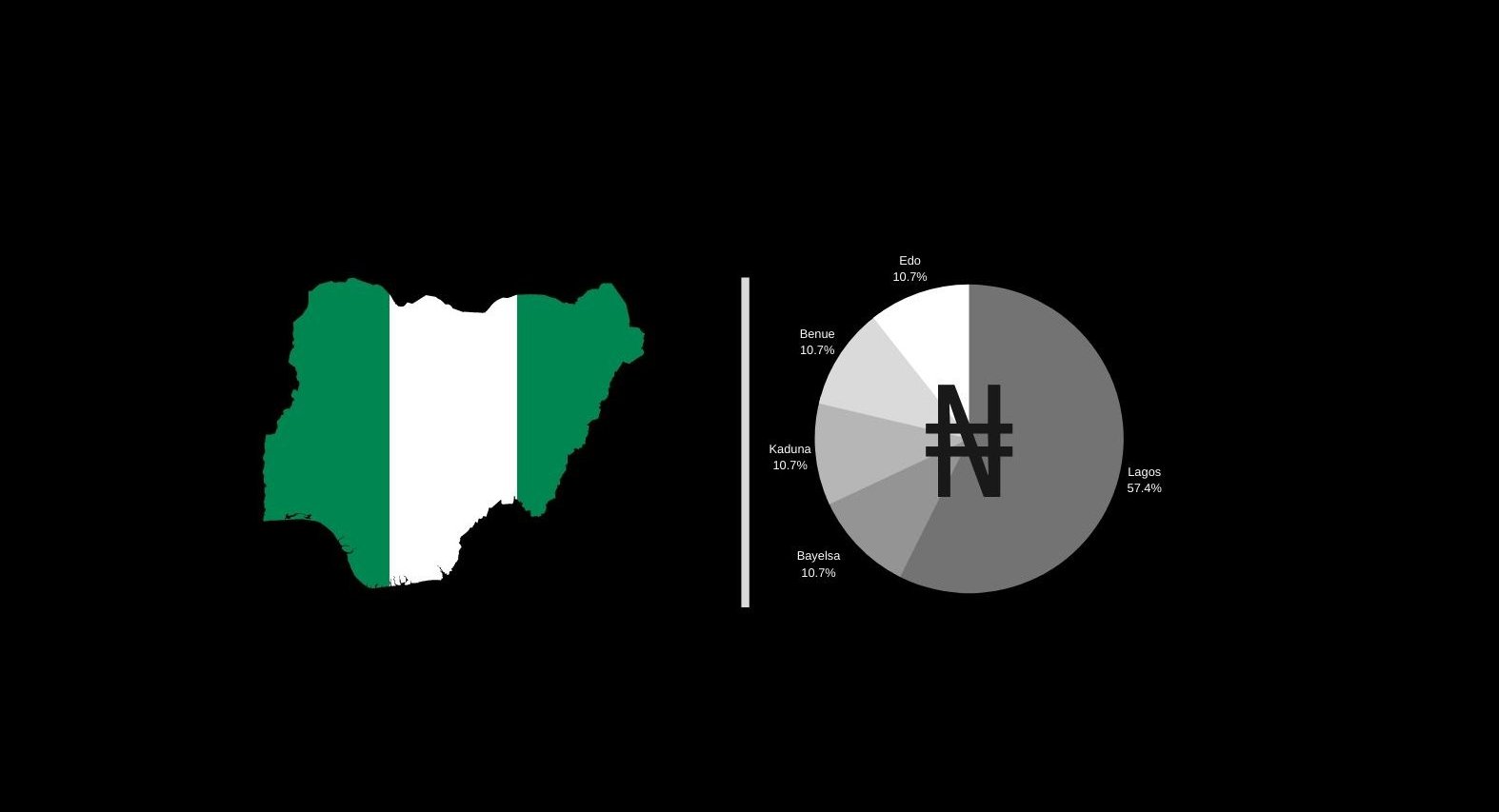

A second look at the revenue allocation model

Demography and structure go a long way in affecting the use and impact of revenue. It is obvious that the present arrangement does very little in reflecting the needs and constraints of federating units. Our census numbers are figures that would always tell half-truths, while the economic capacity of our constituent states would always be a subject of debate but the truth remains that states still require a great deal of funds at least if we go by the fact that irrespective of what the central government does it will not profit every and all states at the same time, in the same way, and on the same level.

It is therefore important to review the current revenue structure with the aim of putting more funds in the hands of those who need it the most to stimulate development on a more expansive and collective scale simultaneously.

State creation and viability

For all the arguments for state creation, there is no messing around with the fact that most states still fail to pass the general economic test of viability. Most states are just creatures of political convenience and are scale-eveners for the politico. However, it is a reality we have to live with and changing it may take a while and a lot more; therefore in dealing with what seems to be our present reality it is advised that we toe the line of inter-state partnerships and commercial alliances for revenue generation. States can partner on a comparative cost advantage basis for income and revenue generation. It is believed that such partnerships can bridge gaps, address the ‘Static-Economy’ or ‘Dependent Economy’ syndrome of most states, and better enhance the scale and level of development across most federating units.

Conclusion

For many years, addressing the dysfunction and deficiency of our Federal system has remained a burning issue dominating discussions at several post-independence constitutional conferences, being the central theme for most pressure groups and lobbyist but yet it still remains an unsolved problem that has in many ways afflicted development and growth on all levels for a country like ours despite the staggering numbers and resources that stand to our credit.

No time is too late to do the right thing and no action is too small provided it is the right one but above all doing the right thing seems to be our best shot at solving this deadlocked equation we have for a federal state. Perhaps, it is time we squared up to the challenge and built for ourselves a thriving federation of independent yet cohesive and self-sufficient units all united by the agenda and ideal of a progressive and inclusive Nigeria for all.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of borg.

The ideas expressed qualifies as copyright and is protected under the Berne Convention.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is notified.

©2020 borg. Legal & Policy Research