Ideas.memo | Samuel Kwadwo Owusu-Ansah

Established amongst the farming communities that constitute the majority of the Ghanaian hinterlands is the practice known as “by day,” it is a custom that is as old as time. It involves the engagement of farmhands for a stipulated period to help a farm owner with the processes involved in the preparation of farmlands for planting.

The defining characteristic of this practice is its payment structure which requires that the engaged farmhands are given a daily wage ergo they are paid “by-day”. This essay will consider whether the philosophy of this old custom used in farming communities may prove a promising prospect for the salvation of democracy in Ghana.

Toward the end of the medieval period, papal rule begun to lose its grip over Europe and the politico-legal identity of Europe was turning away from natural law. By the Renaissance period, Enlightenment theorists such as Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, and Kant had established positivism as the leading political thought in Europe and across the Atlantic. The idea of the emerging social contract theory was that governors of states occupied such office due to the acceptance, unequivocal or implied, of the governed that enabled said governors to make laws to provide rights and ascribes obligations to them. An important question that became apparent following the popularization of the social contract theory was that of sovereignty. Who makes the rules and why do subjects follow the rules that this person makes?

It is pertinent in a quest for these answers to look to the writings of A.V Dicey and John Locke. Dicey in his Introduction to the study of the law of the Constitution (1885) distinguished between legal sovereignty and political sovereignty. The former comprises the sovereign as recognized by the constitutive rules of a particular legal system thence Parliament is recognized as sovereign in the United Kingdom and the Constitutions of republics will self-proclaim their sovereignty (see for example Article 1(2) 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Ghana).

Political sovereignty, on the other hand, is primarily vested in the people themselves and is perhaps best exemplified in democracies by the use of “universal adult suffrage”. It is the basis for which several liberal sources have touted political participation as inexorable from good governance.

"a right of recall will serve as a constant reminder to public officers that their positions are not secured and propel them to act in accordance with their mandate."

It is worthy of note however that there exists a hierarchy in the operation of these skeins of sovereignty. Political sovereignty holds precedence as the legitimacy of legal sovereignty is gleaned from the acceptance of the people. To emphasize this hierarchy, Locke explained that when the representatives of the people were abusing the power vested in them, ‘the people have a right to act as supreme, and continue the legislative in themselves or place it in a new form, or new hands, as they think good’.

The return of Ghana to Constitutional rule in 1993 encouraged the establishment of a host of CSOs which have since worked tirelessly to hold successive governments to account and promote political interest amongst the populace. These initiatives have, to be fair, had immense influence in the political organization of the country post-PNDC rule. They have contributed significantly to the passage of laws and have fundamentally changed the way Ghanaians participate and engage in politics. In collaboration with the media, CSOs have been a significant driver of the stability of democracy in Ghana.

Nonetheless, the activities of CSOs and the media are not enough to attain the standard of participation that is required for a vibrant democracy. There still remains that gnawing feeling of exclusion from politics amongst the voting class which has occasioned a certain apathy for politics. Several reports allude to the fact that political participation in Ghana and indeed across the continent is not impressive.

The low turnout in the recent district-level elections last December and projections of similar turn-out in this year’s general election suggest that only a massive political device deliberately designed to redirect power to its proper depository, the people, will salvage the situation and push the country away from the route of the impending danger that apathy stirs. Such a device is the right of recall.

The right of recall is a political procedure that is rooted in the very history of Athenian democracy and is practiced in various forms across large democracies all through the world including the United States, United Kingdom, Uganda, and with much less efficacy, Kenya. Generally, the right of recall enables voters to recall elected officials from their offices before their tenure has ended.

This essay calls for the country to vehemently explore the efficacy of such a device for elected public officers, to cure the rising trend of apathy rearing its head in the country and to give society more avenues to hold elected officers accountable. Particular note should be taken of Colombia’s Law 134 and similar provisions elsewhere which mandate candidates running for office to issue individual government plans which are subsequently assessed as the primary basis for a recall.

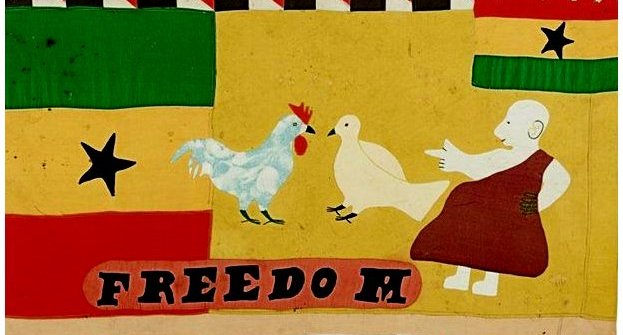

When a candidate is vested with political power and the resources that come with it, the donee of said powers must be conscious at all times of their fiduciary position and their mandate to act solely in the best interests of the electorates who have lent him this power. Such a right of recall will serve as a constant reminder to public officers that their positions are not secured and propel them to act in accordance with their mandate. It is in the exercise of this political device that our native agricultural practice marries with the Lockean insistence on the primacy of political sovereignty as both modes ensure that workers are earning their living day-by-day.

_____________________________________

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of borg.

The ideas expressed qualifies as copyright and is protected under the Berne Convention.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is notified.

©2020 borg. Legal & Policy Research