This issue-brief examines the novel provisions on oil and gas governance and regulation in Nigeria under the Petroleum Industry Bill.

Issue-Brief | Oyin Komolafe

During the first initiation of a Petroleum Industry Bill in 2008, talks flew round the country about the Bill’s potentials to change the trajectory of the oil and gas industry and the state of the country’s economy. Following several sessions of legislative debates, recommendations from committees, and input from the industry’s stakeholders, the bill was still not passed. For several years, amendments and novel provisions have been introduced to the numerous versions of the bill, with no significant improvement.

Amid a situation that seems like a stalemate, the oil and gas industry continues to be governed by obsolete laws, deeply-rooted corruption, and undue bureaucracy. These factors have continually functioned as clogs in the wheel of the development of Nigeria’s petroleum industry. With the Petroleum Industry Bill of 2020, however, the narrative might be set to change.

With the bill’s new provisions, it could potentially chart a new course for oil and gas governance in Nigeria, especially within the context of creating an all-encompassing legal framework to govern the operations in all sectors of the industry, creating a conducive environment for investment, and fostering an industry that aligns with international best practices.

Checks on The Powers of The Minister of Petroleum

For a long time, the oil and gas operations have been largely regulated and governed based on the discretion of the Minister of Petroleum. From granting the Minister’s power to “impose” special terms on licenses and leases, to giving room for the suspension of petroleum operations based on the Minister’s “opinion”, the current oil and gas regime paints a disturbingly dictative system where the Minister has a wide range of discretionary powers with little or no checks in place. The PIB solves this problem.

Like the Petroleum Act 1969(as amended) , PIB states that the Minister may suspend operations in any area where he feels that there has been a contravention of any of the provisions of the Act (currently still a bill), or until arrangements to prevent danger have been made to his satisfaction.

However, the primary difference is that under the PIB, the Minister can only exercise this power upon the recommendation of the Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Commission or the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority.

Similarly, the current legal provision on the delegation of the Minister’s powers, states that the Minister may delegate his powers, excluding the power to make regulations, to “another person”. The danger of such a blanket phrase, which does not have an interpretation in the Act, is that the Minister can indeed, delegate his powers to any other individual asides himself, whether from within or outside the Ministry. The PIB, on the other hand, restricts the options for the delegation of the Minister’s powers to the Chief Executives of the Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Commission and the Nigerian

Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority

However, while these provisions are commendable, they still unduly subject a number of operations to the minister’s discretion. For example, whilst the PIB mandates that a recommendation be made to the Minister before he can suspend operations in an area, the same provision still states that the minister may suspend operations until arrangements to prevent danger has been made to his “satisfaction”. Satisfaction is a deeply subjective concept, and should not be made as a legal benchmark. Instead, an objective expression like “until reasonable arrangements have been made to prevent danger to life and property”, would be much better. It would not only create uniformity but also serve as an investment incentive, as it would assure stakeholders that the industry’s operations are largely separated from the discretion of a single public official.

The Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Commission (NURC)

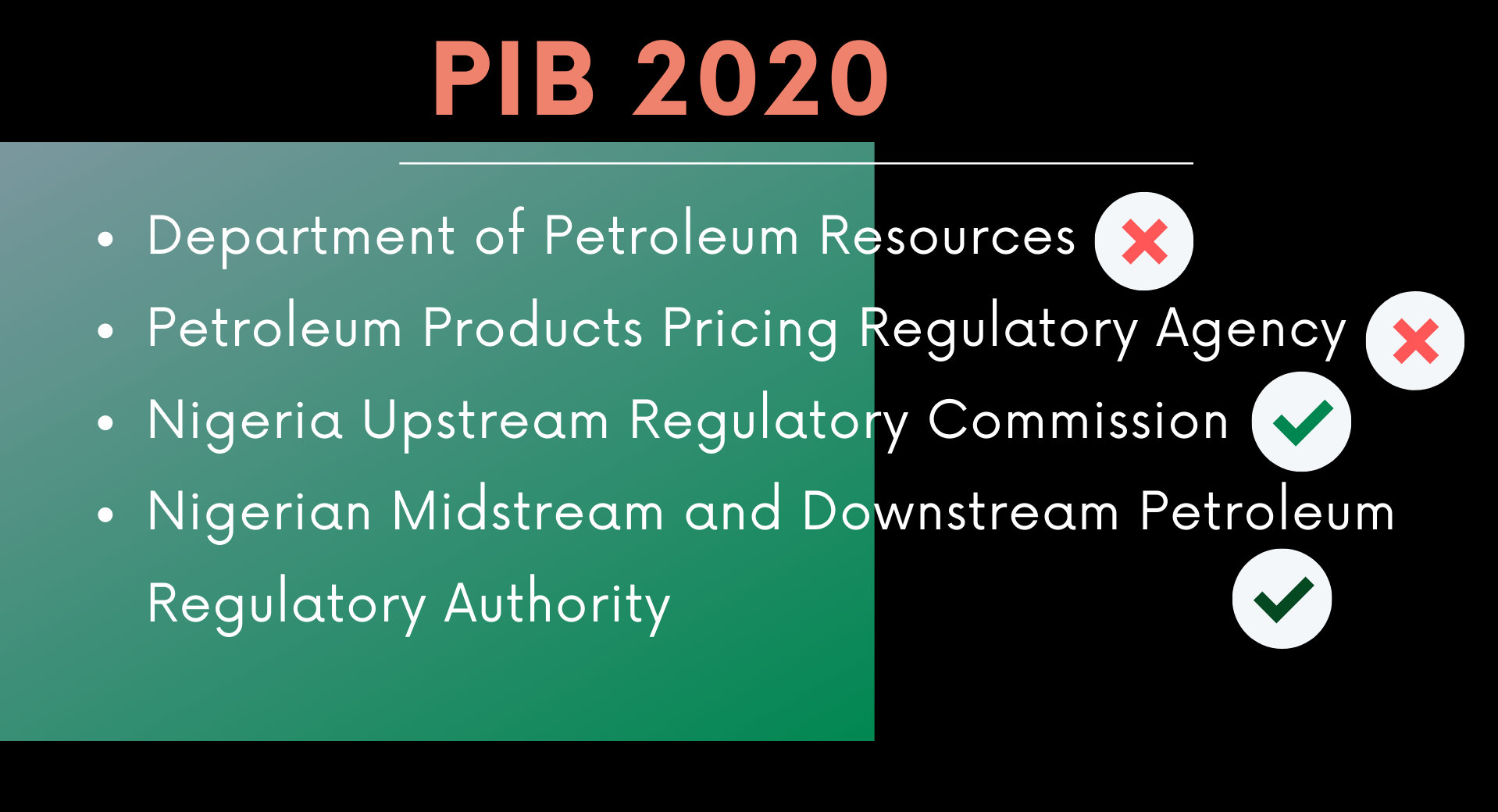

The Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Commission is established under the PIB as the sole government agency in charge of the regulation, governance and administration of the upstream sector of the oil and gas industry. This Commission, which is essentially a replacement of the Department of Petroleum Resources(formerly the Petroleum Inspectorate), will oversee upstream operations including gas flaring, natural gas reinjection and petroleum exploration operations, amongst other operations.

The Commission’s functions are divided into technical regulatory functions and commercial regulatory functions. The former includes administering and enforcing laws relating to upstream petroleum operations and maintaining a Nigerian Petroleum Industry Data Bank comprising materials and data submitted to the Commission. This data bank is not new. It was established in January 2020, through a regulation, as an arm of the Department of Petroleum Resources. Should the PIB be passed, it essentially means that the National Data Repository will be operated by the NURC.

The commercial regulatory functions of the agency include approving commercial aspects of field development plans, supervising cost control in upstream operation and implementing cutbacks on crude or condensate production as ordered by the Minister.

However, in what seems like a renewed attempt to develop oil and gas reserves in Nigeria, the Bill includes the functions of the NURC for frontier basins in the country. Frontier basins are basins with a significant volume of undiscovered resources and where exploration activities have not been carried out. Under the bill, the NURC would function to develop exploration strategies for the exploration of unassigned basins and increase information about the petroleum resources base in the frontier basins. This is a commendable move, considering the government’s new target to increase the country’s oil and condensate reserves to 40 billion barrels by 2025.

The Bill also creates a rather interesting requirement for government agencies to notify the Commission before taking actions or issuing regulations,

orders or directives that may directly impact upstream operations. This may mean that agencies like the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency(NOSDRA) may have to notify the Commission before imposing heavy fines which could significantly increase production costs and possibly hamper production.

The Nigerian Midstream And Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA)

The PIB establishes the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Regulatory Authority as the government agency in charge of both the midstream and downstream operations in the petroleum industry. The Authority’s functions include determining the tariff methodology for processing natural gas transportation and storage, determining the domestic supply obligations, and developing open-access rules for bulk storage facilities and transportation facilities, amongst other functions.

The Authority’s regulatory powers equally span across natural gas trading and export, dispute resolution and customer protection, competition, and the processing, storage, and supply of petroleum products. Quite interestingly, the Bill also includes special powers for the NMDPRA. These special powers are basically investigative powers with which the Authority will be able to crackdown on companies and persons involved in illegal midstream and downstream operations like oil bunkering. These powers are to be exercised by the Special Investigation Unit of the Authority.

Inclusive Governance

In an attempt to boost stability and fully involve the industry’s stakeholders in the governance process, the Bill mandates both the Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Commission and the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority to consult with stakeholders (licensees, lessees and permit holders) before finalizing or amending any regulation. To kick-start the consultation, the Bill requires that a notice be published on at least, two national newspapers as well as the agencies’ websites, detailing the venue, time, subject matter, and other important pieces of information.

However, the Bill also creates an exception to this provision, which stipulates that in cases of national interest, both agencies will be able to make laws without the required consultation, subject to the fact that such regulations would only be valid for a maximum of one year, unless the agency carries out the consultation process.

This provision is much needed, as one of the major factors hindering investment in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry is the inconstant regulatory regime. With the adoption of this provision, investors would not caught off-guard by regulatory changes. This would, in turn, facilitate considerable stability in the petroleum industry.

Conclusion

With the dwindling demand for oil and gas and the imminent global transition to renewable energy, the need to fully harness Nigeria’s oil and gas industry is more urgent than ever. However, with the current regulatory regime which is being operated, there is a high probability that Nigeria’s oil and gas potentials will not be attained. The PIB 2020 presents a fresh opportunity for Nigeria to restructure its petroleum industry, create an investor-friendly environment, and effectively profitize its oil and gas reserves.

This is part of our series on #ThereIsABillinTheHouse.

This issue brief was provided by

Oyin Komolafe | Research Assistant, Energy | k.o@borg.re

Our issue-briefs provides a platform to provide commentaries on knowledge surrounding a current relevant local or transnational discussion.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of borg.

The ideas expressed qualifies as copyright and are protected under the Berne Convention.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is notified.

©2020 borg. Legal & Policy Research